Part 2 in a 3-Part Series on How To Parent Your Anxious Child from Linda Gieger

Parenting your anxious child is often a traumatic experience for both parent and child.

Parenting your anxious child is often a traumatic experience for both parent and child.

It is a frustrating, maddening, and heartbreaking endeavor that often generates parental discord and family dysfunction. Moreover, it can set parents against each other as their contrasting styles come into stark conflict. Usually, one parent exhibits a more disciplinary approach, while the other is more understanding and permissive. However, with an acutely anxious child, neither strategy works.

The lesson we need to absorb rapidly is that standard parenting techniques won’t help your acutely anxious child.

We cannot rely on parenting skills developed for other children. In fact, many of the parenting methods we have all painstakingly developed will likely be counter-productive. When faced with severely anxious adolescents governed by their amygdala, time-tested positive reinforcement strategies, firm guidance, and natural consequences fail. Instead, our approach needs to be tailored to the uniqueness of the acutely anxious child. The methods we need are counter-intuitive and fly in the face of many of our parental instincts and hard-won parenting proficiency. A different approach, informed by professional help, is much more effective.

My earlier article focused on helping parents understand and recognize acute anxiety disorders.

In that article, I relayed my story and mentioned that a-ha moment of clarity when I realized my 15-year-old son’s problems were medical, not behavioral. He was not choosing his behavior; his medical condition was dictating it. In common with most medical conditions, treatment of acute anxiety disorders can never be based on a “one size fits all” approach. Every acutely anxious child is unique, and the condition manifests itself in various ways, such as perfectionism, panic attacks, and school avoidance. This article offers some practical advice informed by a combination of my own painful experience and the support of the Anxiety Institute’s team of experts. I hope you will find it helpful in your journey.

Transitioning from Accommodation to Support

The most perplexing challenge in parenting your anxious child is differentiating between accommodating them and supporting them and then transitioning from one to the other.

Of course, once you know your child is suffering from acute anxiety, accommodation feels like the kindest option. But, like any illness, improvement only comes with treatment. So, as parents, we need to make this subtle transition from accommodation to support.

Many parents struggle with this tough transition. After all, you have built and reinforced your responses to your child’s behaviors over many years.

Although accommodation seems easier, it creates its own challenges that make treatment and recovery harder for many reasons.

- First, accommodation increases dependence. It protects the child from unwanted feelings of anxiety and discomfort or prevents negative consequences. The child then cannot establish a method to address their feelings for themselves.

- Accommodation also conveys to your child that they can’t manage without your help – reinforcing doubts about their own ability to cope.

- Finally, accommodation creates further dependence as you anticipate what can go wrong and intervene to “fix it,” whether your child needs help or not.

Conversely, support has lasting benefits.

- Support increases autonomy. It doesn’t avert calamities or failures, nor does it prevent those anxious feelings from surfacing, but it starts to help your child deal with those feelings and disappointments themselves.

- Support also sends a powerful message – that you believe your child can handle the challenges and consequences of a given situation. It places trust and starts to build confidence.

- You provide support in response to your child’s request; it’s not something for which you volunteer. In this way, your child learns from the help they receive – they requested it.

Gradually, these adjustments create new patterns of interactions between you and your child that will ultimately become habitual. However, the path from accommodation to support is not a smooth one. As you migrate to this new approach, expect some anger and rebellion from your child. This reaction is entirely natural as they feel entitled to the accommodations you are no longer providing them.

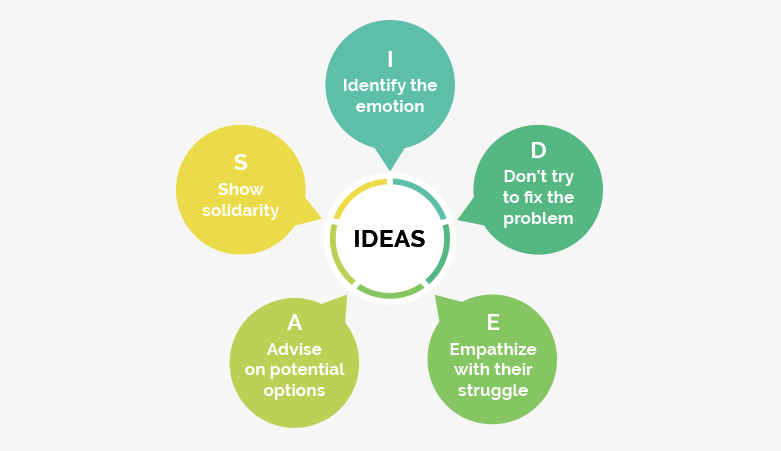

In my own painful parenting journey, from accommodation to support, I developed a simple framework that I called IDEAS.

First, I will share this framework and suggest some general communication rules, particularly concerning what not to say. I learned these techniques from my colleagues at the Anxiety Institute. Finally, I’ll identify some physical responses our therapists at the Anxiety Institute recommend that can calm and support your anxious child.

The IDEAS Framework

IDEAS is a simple five-step process I refined through trial and error to engage with my son and guide him when his acute anxiety symptoms manifested themselves.

This process eventually facilitated some productive conversations and prevented me from falling into old traps or overly prescribed solutions which rarely helped. The objective of these interactions is to transition from accommodation to support and empower your anxious child to become increasingly resilient and independent.

I

Identify the emotion

Anxiety can manifest into different emotions such as anger, frustration, fear, or total emotional shutdown. You may not even recognize the emotion your child is experiencing. In this case, accept the confusion and resist the urge to judge or explain why they feel the way they do. Instead, approach the situation dispassionately, like an emotional scientist. Your goal is to understand the underlying emotion and circumstances surrounding it. During your conversation, state what emotion you think your child is feeling: “It sounds like you’re really [frustrated/angry/sad/anxious/etc.]”, then allow your child to course-correct as needed. This exercise helps them think somewhat rationally and thereby clarify their feelings.

D

Don’t try to fix it

This is the most challenging part for many parents. It is very tempting to suggest solutions and quick fixes immediately. However, your child must develop the skills to problem solve on their own.

E

Empathize

Create an empathetic bond with your child, even if you don’t understand their heightened emotion. Communicate that you know what they are struggling with and how difficult it is for them. Saying something like, “Wow, that sounds real hard,” is a great start. The goal is to connect with their experience.

A

Advise

Once you have correctly identified the emotions and established a personal connection, help them to brainstorm possible solutions. Start with some basic questions. “What do you think you should do about it?” “How do you think you are going to handle it?” “What else do you think you might do?” If asked, you can help refine your child’s ideas, but your child must “own” the solutions to their situation. This also signals that you have confidence in their ability to navigate the situation and becomes a teaching moment in nurturing their independence and resilience.

S

Show solidarity

Lastly, communicate that you are available to help. At the same time, emphasize that you fully believe they are capable of handling the situation. They are not alone, but they are capable on their own. “You can handle this, but I’m here for you if you want advice” is the key message that you want to convey.

Communication Guidelines

When talking to your acutely anxious child, there are some additional communication guidelines you should bear in mind:

Don’t ask why.

This advice might appear counter-intuitive, but to quote Anxiety Institute co-founder, Dr. Dan Villiers:

“It’s counter-productive to ask your child why they are anxious. In almost every case, they won’t be able to identify the source of their anxiety”.

It is essential to uncover the source of the anxiety, but asking an acutely anxious child is seldom a helpful approach.

Don’t tell your child to relax.

Instead, just be present for your child and sit with them quietly. If possible, suggest that they check their pulse to see the pattern of accelerations and deceleration.

Provide assurance by being present.

Calmly remind your child that the symptoms won’t last by recalling how the symptoms occurred before and that they recovered successfully. Tell your child that you will work on this with them and that they are not alone on their painful journey. Not only does this approach help support them, it potentially offers them the chance for a better outcome than their last incident, shifting their thoughts towards a feeling of gratitude for your unconditional support.

Physical Activities

These psychological and conversational approaches require time, energy, and support. An adjunct strategy is to complement these approaches with physical activities, many of which have demonstrably beneficial effects.

Breathing Techniques

During many anxiety attacks, the sufferer has fast and shallow (thoracic) breathing that causes muscle tension, increased heart rate, and dizziness. Therefore, it’s vital for them to find their normal rhythm. One way is called “lion’s breath,” whereby they sit comfortably, inhale through the nose, exhale through the mouth with the tongue out, releasing the sound “ha.” Other options include alternate nostril breathing, belly breathing, box breathing, and mindful breathing. The critical point to remember is that each method is a repetitive process of inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth.

Stimulate the Vagus Nerve

Stimulating the Vagus Nerve, situated on both sides of the voice box. This technique aims to disrupt the body’s fight-or-flight response. The nerve can be stimulated by chewing gum, eating, singing, humming, chanting, socializing, laughing, or meditating.

Use Sensory Focus

This is a technique designed to shift your child’s focus from anxiety to calm. Anxiety paralyzes them; calming occurs when they can focus. For example, one exercise could be to ask your child to name items around them that they can see, smell, touch, hear, or feel. This relaxes the body by narrowing the child’s attention. You can also use visualization or imagery to guide the child back to their normal state, such as a happy place, person, or activity.

Move

Physical activities act as distraction techniques that can relax your child. Indulge your child with physical activities that center the child’s attention, like running up a flight of stairs, running around the block, or doing jumping jacks. You could also try slow movements like taking a walk, going for a hike, or doing yoga. However, these exercises are often long-term solutions rather than quick fixes.

Show Physical Empathy

Show physical empathy by hugging or holding hands. Demonstrating compassion through physical touch releases oxytocin, the feel-good hormone, reducing anxiety and restoring calm. One study on the mutual regulation between oxytocin and cortisol revealed that oxytocin exerts stress-buffering effects, reducing stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity and decreasing cortisol levels in the body. Meaning, the oxytocin hormone can calm the body while releasing stress and anxiety.

Hopefully, some or all of these approaches will help your acutely anxious child. Eventually, they started to work for me. Absent professional help, trying some of these approaches will help the healing process and enable you to see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Conclusion

Supporting a child suffering from acute anxiety is challenging for many parents. However, once we understand the condition, treating it will improve your child’s biological development.

In addition, you will help them build skills that will empower them to analyze and accurately process difficult situations for the rest of their lives. You are supporting, not accommodating.

Of course, every complete therapeutic solution requires a unique approach tailored to the specific needs of every child. The techniques described above, both psychological and physical, can be customized to your personal situation and pave the way from accommodation to support. My hope is that your child will develop the skills and awareness required to overcome whatever new challenges they encounter as they grow.

About the Author:

Linda Geiger, CEO & Founder of the Anxiety Institute:

Linda Geiger is a highly experienced business and operations strategist with expertise in start-ups, both stand-alone and within complex organizations. Linda also has a significant background in financial turnaround for troubled companies, functions, and divisions. She brings a proven business track record in market strategy, marketing, and product development.

Linda is currently on the Board of Directors for a non-profit organization focused on leading-edge anxiety research, training, and education. She also served as an officer in the PTA and as a board member for over eight years for the Los Altos Educational Foundation (LAEF), a non-profit that funds enrichment programs and supports more effective learning environments through reduced class size.